What is the cost of complacency when it comes to your Superannuation?

Many Australians, in particularly the younger ones, are so totally disengaged when it comes to Superannuation that they are not aware of what super fund they belong to, how many accounts they have with different super funds and how their super is invested.

Do you fall into this category?

Disengagement with super is highlighted by the fact that in 2017/18 the Australian Taxation Office was holding around $17.5bn of lost superannuation. This was spread over $6.2milion separated accounts, with the largest single account being $2.2m for a New South Wales individual.

Even if you don’t have any lost super and know how much you have, there are other things you need to be aware of that can have a significant impact on just how much you will have in super when you reach retirement.

Things like, how your super is invested, and the amount of fees you are paying can seriously impact how comfortable your retirement will be.

For many Australians, their compulsory superannuation contributions are being paid to a super fund nominated by their employer and is being invested in accordance with the funds’ default investment option. The super fund selected, and the investment option may be totally inappropriate for an individual member of the fund.

When we talk of investing money, we must take into account what is referred to as our “risk profile”. That is, are we someone who doesn’t like to take unnecessary risks with our money and therefore may be a conservative investor, or are we someone you is prepared to take considerable risk to see our super nest egg grow and therefore be a “growth focused” investor, or do we sit somewhere in the middle ground and are a “balanced” investor.

Many default superannuation funds have a balance investment of option as their default. But what is a balanced fund for one super fund may mean something entirely different for another super fund.

Being a member of a default balanced fund may be fine for someone who is willing to take some, but not a lot of risk in the manner in which their super is invested, but it may be totally inappropriate for a member who is approaching retirement and may feel more comfortable with a less risky approach to their investments, or for a younger member who has many years to ride out the ups and downs of the investment markets in exchange for a potentially higher return.

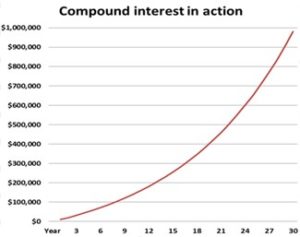

Selecting an appropriate investment option for their super becomes an important consideration for members of superannuation funds. An additional 1% or 2% annual investment return on superannuation savings can make a difference of hundreds of thousands of dollars for a young superannuation fund member, over their working life.

Another aspect of super that cannot be ignored is the fees being charged by super funds to manage your money. While fees for many super funds have been reducing over recent years, there are still many super funds that are charging fees in excess of those offered by their peers.

Just as an additional 1% or 2% of additional investment return can have a positive impact of a superannuation balance, paying higher fees than necessary can have a significant negative impact on superannuation savings over the course of a working life.

As a member of a super fund, you need to be aware of what is happening with your super.

Here are some questions to consider:

1. How many super fund accounts do I have? If more than one, should I consolidate them into one fund? This can save on fees – but check that you are not losing valuable insurance cover first.

2. Do I have any lost super? This can be checked by logging in to your MyGov account or asking your existing known super fund to check for you.

3. What fees am I paying for my super? In particular, am I paying fees for services I don’t need?

4. How is my super invested? Is it appropriate for my life stage and my own attitude to risk?

5. How has my super fund performed over time? Don’t simply keep chasing last year’s best performing fund but look to a super fund that provides consistent returns over a longer period and charges a fair fee for the services they provide.

For many people, analysing the appropriateness of their super fund will not be an easy task. However, help from a suitably qualified financial adviser to ensure you are, or get you back on the right track may be money well spent.

Source: Peter Kelly | Centrepoint Alliance